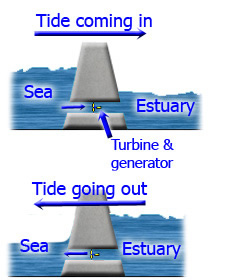

To bring up a well known local example, the green

crab (Figure 1), it is clear that these small invertebrates cause much damage

to new areas. Originating from Europe they have reached the up to North Harbour

and Placentia Bay. There have been reports of hundreds of unusual crabs to

federal fisheries officials. They have already altered coastal environments

around the Maritimes, British Columbia and the east coast of the United States.

At the beginning of the discovery of the green crabs existence in Newfoundland

the results have been troubling due to the natural aggression of green crabs and they are displacing the

native red rock crab by out competing it and eating just about everything else

along the ocean bottom. Many departments are working to understand the damage

that is being done and what can be done about it, theses departments vary from

the scientists from the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Memorial

University and the Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Fisheries (Kern,

2002). And it has been discovered that the most likely scenario of

anthropogenic transportation of these crabs is by the larvae getting into

ballast tanks of ships which then get transported to various bays.

Figure 1: Green

crabs located in NL. Photo from DFO Canada

This species also is on the top 100 list of invasive

species based off of Australia’s experiences with the green crab which over

took many native crabs and introduced new parasites to the area From research

done in California, these crabs have been found to reduce competing predatory

and fish-farm populations. They discovered the crab thrives in a wide range of

coastal environments and can endure high and low water temperatures, and

salinity-levels that would feed on many local organisms. And it has also been

found that in areas where human activity has reduced seawater salinity, such as

estuaries and port-lands, the green crab easily out-competes other seafloor

predators (Homes, 2001).

This is not just a Newfoundland problem it has also

been problems on all coasts of this nation

In Prince Edward Island, the eel fisheries have

collapse due to the over grazing by green crabs and green crabs swamping the

eel pots and therefore not ever letting fishermen catch eels.

The management thus far focuses mainly on preventing

primary pathways such as new introductions, and also block secondary pathways

such as anthropogenic reason. Educational effects are also a major concern and management

tool in preventing further introductions. As for controlling the population

currently is through eradication and mitigation techniques until further plans

of control are evaluated (Kern, 2002).

Well we have discussed

many different case studies of invasive marine species both here in

Newfoundland and in the wider world. And let’s face the facts, Newfoundland

does seem to be lagging behind some of the other regions’ efforts, but

generally there is nowhere near as much effort as is needed to start making

progress on this issue. We do have organizations and government departments

that are working on management plans and implementation but it’s not enough. We

don’t even know enough about these invasive species to properly handle many of

these problems; more funding is needed to study them and learn how best to deal

with them. But by far the largest problem is keeping the public educated. Most

residents of the province don’t even consider the fact that marine invasive

species could be a problem. A simple but major way to reduce introduction and

spread of new invasive species is to regularly check and clean the bottom of

boats, but many people don’t bother because they simply don’t understand the

consequences of these various exotic species. If we could help them understand

and gain their support, it could go a long ways in helping with aliens such as

this green crab.

Just

so we don’t leave on a bad note... We encourage you to spread the word of this

growing project and maybe even see if you can help with any initiatives to

mitigate some of these problems. There’s a lot of work, but if everyone pitches

in we are much more likely to start making some progress J

Further Readings:

Homes, D. (2001) The Green Crab Invasion: A Global

Perspective, with Lessons from Washing State. National Association of

Environmental Professionals Retrieved from: http://academic.evergreen.edu/h/holmesd/

Kern, F. 2002. Management Plan for the European

Green Crab. Green Crab Control Committee. Retrieved from: http://www.anstaskforce.gov/GreenCrabManagementPlan.pdf

DFO,

Canada. 2010. Aquatic Invasive Species: European Green Crab In Newfoundland

Waters. 978-1100-14903-. Retrieved from: www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/science/Publications/article/2008/10-06-2008-eng.htm